At Evelyn Gonzalez’s Denver high school, the Italian teacher, who luckily speaks Spanish, filled in last week for the Spanish teacher, who was out sick for two days.

So many students were absent from Haven Coleman’s history class at another high school that the teacher held off on teaching the day’s lesson rather than have to repeat it later for the missing kids. Coleman’s class had a study hall instead.

In Carbondale, an entire grade level at Crystal River Elementary switched to remote learning, not because teachers were sick, but because several of them were also parents of preschool-aged children quarantined at home.

If this past fall felt “mostly normal,” Assistant Principal Kendall Reiley said, then after winter break, “it felt like we were coming back into a different world.”

January’s massive COVID surge has tested pandemic-weary teachers, students, and families in new ways, with half-empty classrooms, missing teachers, and abrupt temporary switches to remote learning, often for just a number of days.

District leaders have mostly kept buildings open amid case rates that would have shuttered them a year ago. They cite the availability of vaccines, plus widespread concern about the toll virtual learning took on children’s mental health. Relaxed safety protocols are also giving schools new tools to stay open, like combining classes and shortening quarantine.

That doesn’t mean the past few weeks have been easy. Interviews with 20 Colorado students, parents, teachers, principals, and district administrators provide a window into disrupted learning and reveal deep divides over the best way forward. Some students say they’re worried about catching the virus but also dread a return to virtual schooling.

“Going remote learning is like going a step back to the past,” said Andrew Caballero, a sophomore at Denver’s Abraham Lincoln High School. “Students should be able to go to school and interact with other students and not be home 24/7.”

Keeping schools open requires constant juggling

For Shane Knight, principal at Denver’s Knapp Elementary School, the text messages start at 5 a.m. and go until late. At first, he and his assistant principal were keeping track of sick or absent teachers on a whiteboard, marking those who were out with COVID with a red “C+.”

They later moved that accounting to a spreadsheet, but the logistics of who was absent and who was covering their classes became so unsustainable that Knapp temporarily switched to remote learning, one of more than 45 Denver schools to do so in the past three weeks.

“As soon as I informed my staff, the tension in the building dropped dramatically,” Knight said. “It was palpable. They were on edge like, ‘Who is leaving next?’”

It’s a feeling teachers from across Colorado said they know well.

Cara Godbe teaches a combined second and third grade class in Montrose. Vaccination means some students who would have had to quarantine in the fall can now stay in the classroom, but that presents its own challenges.

“I might have eight kids who are eligible to stay in the classroom, and 16 that are not,” she said. “And that puts teachers in a bind. How do you teach both groups of kids?”

When the third grade teacher at Kate Tynan-Ridgeway’s school, Palmer Elementary in Denver, was out with COVID right after winter break, she and the other second grade teacher split his class, adding 10 more kids to each of their rooms.

Instead of teaching the regular second grade curriculum, Tynan-Ridgeway said, “I was inventing my whole day. It was like, ‘Let me adapt this. Let me adapt that.’” Though the students were still getting academic instruction, it wasn’t what they’d normally learn.

The next week, Tynan-Ridgeway had to miss school because of her own COVID exposure.

Who’s in class

It’s hard to get a clear picture of full and partial school closures because Colorado doesn’t track them. Some districts told Chalkbeat that student and staff absences were similar to those in the fall, when Colorado endured a prolonged delta wave. Other districts reported a dramatic increase in COVID cases, lower attendance, and many teachers out sick.

The Adams 14 district in Commerce City went remote the second week of January, but opened most of its schools this week. Bayfield in southwestern Colorado canceled all classes and activities this week after a fifth of the entire teaching staff either tested positive or entered quarantine.

In the Greeley-Evans district, more than 300 staff members have tested positive so far this month, sending five schools, including one charter, into remote learning due to staffing shortages. In Aurora, student attendance hadn’t changed much, but staff absences were up 52% in January compared with the fall average.

“We meet every day around 3:45, 4 o’clock, to assess where we are for tomorrow and then tomorrow comes and the facts change on us and so we are trying to think very nimbly,” Aurora Superintendent Rico Munn told the school board.

Lack of substitute teachers is a major problem. In District 11 in Colorado Springs, almost half of teacher absences went unfilled last week. Many districts are dispatching central office workers, many of whom were never teachers, to help at schools. Denver sent out 500 of them a day, prioritizing coverage for schools at risk of closing.

Some teachers and students have said a short period of remote learning would provide more stability and question whether the disruption involved in keeping schools open is worth it. Amber Elias, Denver’s lead operational superintendent, believes it is.

“As much as our primary purpose is instruction, we provide so many more benefits,” Elias said. “I keep going back to the research that shows students are physically, mentally, and emotionally safer in school. We would rather keep kids in school when we can. We know we are not able to provide that quality of instruction that we would at full staffing, but there are a lot of other benefits to school.”

Some students find it hard to forget about COVID

Anoushka Jani spent all of last year online, worried about bringing COVID home to her family. She returned to Legacy High School in the Adams 12 Five Star school district in the fall as a vaccinated senior eager to make up for lost time. She attended football games and sought out unfamiliar students so she could get to know as many people as possible before she graduated.

Omicron has taken away that sense of ease. When she walks through crowded hallways or hears someone cough in class, she finds herself wondering if she was exposed.

“Coming back from winter break, I can hear in the hallways, kids are talking about their friends testing positive,” she said. “There are a lot fewer kids in classes. There are teachers out. There is a looming dread that we might go back online.”

Jason Hoang, a senior in Aurora, decided to quarantine last week after finding out that a friend he sat next to in multiple classes tested positive for COVID. The quarantine wasn’t required, but Hoang felt it was the right thing to do. Some teachers offered him a way to participate in classes remotely, but others just gave him assignments to do on his own at home.

“I’m surprised we’re actually still in person considering how COVID numbers have skyrocketed,” Hoang said. “I prioritize safety. I wish the school did that as well.”

Freshman Nayeli Lopez is one of several Denver Public Schools students who wrote an online petition demanding the district take additional safety measures, including providing students with the more protective KN95 masks, twice weekly COVID testing, and more flexibility to learn from home when school doesn’t feel safe. On Thursday, some students at North High School and Thomas Jefferson High School walked out of school in protest.

Lopez, who goes to North, said she’s so worried about COVID and so frustrated with the district response that she can’t concentrate in class.

“I feel that they’re giving up on us,” Lopez said of district leaders.

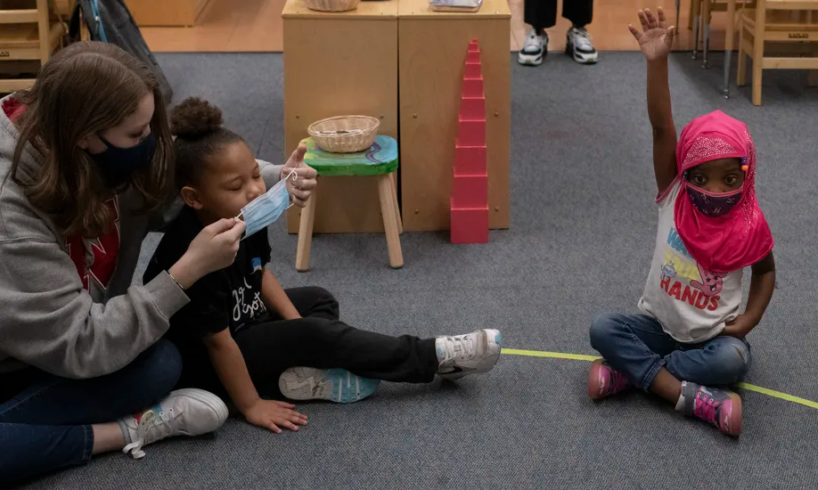

Denver officials are distributing KN95 masks to schools, including smaller ones for young children, but believe that the safety measures they’ve employed all year continue to keep schools safe.

Teenagers have the highest COVID rates in the state right now, according to public health officials, and child hospitalizations are at record levels. State Epidemiologist Rachel Herlihy said some transmission is occurring in schools, but also at home and in social settings. The best protection, she said, continues to be vaccination.

Many school districts have shortened quarantine requirements under new federal guidance in an effort to keep students and staff in person, even as some teachers worry that the constant shuffle is contributing to more spread. Colorado school districts have a wide range of mask and quarantine policies, and officials everywhere say their schools are safe.

Denver leaders point to universal masking and the district’s 99% staff vaccination rate as limiting transmission. Mesa Valley District 51 requires masks when more than 2% of a school population tests positive. In Cañon City, students “on quarantine” after an exposure can come to school if they agree to wear a mask.

Isenia Fregoso, a junior at Central High School in Mesa County, also worries about COVID, especially after her mom got sick over the holidays despite being vaccinated. She feels safer now that her school has a mask requirement, and she would rather be in school.

“Adults need to realize that it’s really hard for students to stay engaged even in person, and it’s even harder to keep that momentum and motivation online,” she said. “You’re just alone and it feels different. The experience does matter and the setting and what students are used to when it comes to being in school.”

Parents are making their own decisions about school

Emily Stone got an email that her third grade son had been exposed to COVID on his first day back in school from winter break. Although he and his older brother are vaccinated, Stone decided to keep both home last week due to rising case counts.

The decision was based on something her third grader asked her after he was exposed. “My youngest said, ‘Mom, can you tell me I’m really safe at school?’” said Stone, who lives in Denver. “And I couldn’t say yes. I was like, ‘I don’t know, kiddo.’”

Other parents said they’re more resigned to the situation.

Michelle Squier’s 14-year-old son, who is vaccinated, got COVID in early January, a week after his mother and older sister contracted the virus. He missed several days at Bell Middle School in Golden, and when he returned, a teacher noticed his residual cough and he was sent home for another day and a half. This week, he’s back in class.

“That’s just life right now,” Squier said. “We’re all in that boat. We’re all together.”

Ana Jelly Melchor, a mother of two Aurora students, said she’s weary of teachers taking sick time and frustrated that her children have missed out on opportunities. Her older son told her that he was denied a schedule change to take college-level courses due to COVID concerns.

“He has all A’s,” she said. “When I had parent-teacher conferences, the teachers said that he needed to be in college-level courses, something more advanced, but they haven’t sent him.”

‘Teachers are doing a lot’

This week, Herlihy said it appears omicron has peaked in Colorado and new cases are heading down. Administrators in some metro area districts also said it seemed they had turned a corner, with fewer staff calling out sick and just a handful of classrooms on remote learning.

Coza Perry, who teaches sixth grade English at a middle school in Denver, said knowing the disruptions are temporary has made this month feel more hopeful than fall semester. In the fall, some teachers were gone for long stretches because they were unhappy and eventually quit. This semester, with a more stable staff and several months of in-person learning under their belts, “little moments of joy are starting to creep back up,” Perry said.

“Before, the tension was, ‘You’re out and I don’t know if you’re sick and I don’t know if you’re coming back,’” she said. “Now it’s like, ‘OK, I can handle covering a science class for three days and I know the science teacher is coming back.’”

Cañon City Schools made changes to their procedures in the fall that took some of the burden off principals, and it made a big difference in their ability to manage COVID.

“The pandemic has absolutely been a huge stress on education,” Superintendent Adam Hartman said. “It’s a huge pressure on staff. But it’s important that it not be all gloom and doom. We are dealing with omicron and the numbers are up, but we are persevering.”

Godbe, the Montrose teacher, said it’s almost scary how well her students and colleagues can “turn on a dime” two years into the pandemic, but she worries it will just become expected. She knows open schools keep society functioning and allow parents to work, but the new reality also raises questions about the role of teachers.

“Are we essential workers? Are we babysitters? Are we professionals and experts?” she asked. “Teachers are doing a lot for communities right now, and it would be great if that could be acknowledged.”

This article was originally posted on Colorado schools bend but don’t break under omicron surge