Two years after a historic “flip” of the Denver school board, the teachers union is spending big in next week’s election in the hopes of hanging on to a political majority. That majority has allowed the current union-backed board to undo or halt controversial reforms put in place by its predecessors, including closing low-performing schools and expanding autonomous ones.

Meanwhile, local and national organizations supportive of education reform strategies are spending even more to elect school board candidates they believe align with their vision.

It’s a familiar dynamic, and one that has played out in Denver school board elections for more than a decade. In a non-partisan race where most candidates are liberal and every candidate says they want the best for kids, it can be difficult for voters to see the distinction.

That distinction may indeed be getting blurrier. Reform-backed candidates in the Nov. 2 election aren’t talking about closing struggling schools, while union-backed candidates have toned down their criticisms of charter schools. Some send their own children to them.

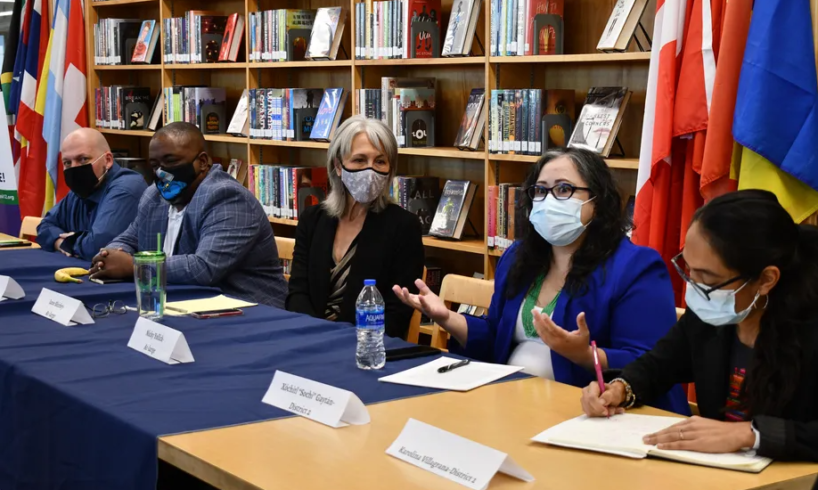

When students from Denver’s John F. Kennedy High School hosted a candidate forum this week, they said the candidates largely agreed with each other on topics like mask mandates, sex ed, charter schools, and serving students with disabilities.

“They were having conversations using ‘yes, and,’” said Priscilla Pauda-Perez, a junior at Kennedy who’s a member of the student board of education.

Instead of debating, added senior Melanie Valadez, “it was more like building off each other.”

But despite the muted rhetoric, the differences between the actions of the union-backed school board and those of previous reform-backed boards are stark — and help explain why the battle for control of the Denver school board could be a multi-million-dollar fight.

“This election will answer the question of whether the district continues on its current path of moving away from the reforms and toward this other conception of the district that the current board has been trying to articulate,” said Parker Baxter, director of the Center for Education Policy Analysis at the University of Colorado Denver. “Things like the district’s posture toward charter schools in general is still very much at stake, even if the rhetoric does not make that clear.”

Eternity Lomeli, a senior at John F. Kennedy High, put it more plainly.

“What’s at stake is our future,” she said.

A history of reform

Starting in the mid-2000s, the Denver superintendent and school board put in place policies aimed at improving test scores and stemming declining enrollment.

Those reforms included tying student test scores to school ratings, and closing schools with low ratings. The board also nurtured the expansion of high-scoring charter schools, which are publicly funded but independently run. Denver now has 58 charters, accounting for about a quarter of all schools. The district made it easier for families to choose charters and other schools outside their neighborhood by adopting a common application districtwide.

Whether the reforms helped or hurt is fiercely debated. Test scores improved over time, but wide gaps persist between the scores of white students and Black and Hispanic students.

Some of the reforms also fostered mistrust between the district and affected communities. Most closed schools served low-income communities of color, and many families and teachers felt their pleas for help were ignored. Wariness of the district persists in those neighborhoods, even if more students who live there graduate and go to college now than did before.

Some see the district’s encouragement — and in some cases, requirement — that families research and choose schools as creating unhealthy competition. Others see it as a way to empower parents and boost student success.

The Denver teachers union has long criticized charter schools for siphoning students and per-pupil funding from the traditional district-run schools where union members work, and some think charter expansion is a union-busting tactic. Charters have waivers from certain state and district rules that allow them to operate more autonomously but some see as unfair.

The union has similar concerns about innovation schools, which are district-run schools that can waive some of the same rules and opt out of parts of the union contract.

But the families whose children attend these schools and the staff who work at them say such autonomy allows the schools to be more responsive to students’ needs. If a school wants to extend its day until 4 p.m., the union contract isn’t stopping it. If it needs to hire more special education teachers, it has the budget flexibility to do so. If it wants to change its curriculum to include more Black history, it doesn’t have to fight through district red tape.

A three-day teachers strike in 2019 was partly a backlash against reforms unpopular with union members. Union-backed members won control of the board in that November’s election.

And in the past two years, the board has made some big changes.

A new direction

The board started by taking a softer tone with low-performing schools, giving them a chance to show improvement instead of moving swiftly to close or replace them.

Board members also voted to reopen two comprehensive high schools in communities of color — West High and Montbello High — that previous boards had dismantled.

The board approved a new labor union for principals and got rid of the controversial school ratings system that had been used to justify closing low-scoring schools.

Board members attempted to delay the opening of a new charter high school put forward by Denver’s largest homegrown charter network, DSST. However, the board’s vote was overturned when DSST appealed to the State Board of Education.

The Denver board did delay the expansion of two autonomous innovation zones by denying more schools entry. Although the schools inside the zones are district-run, they are overseen by nonprofit organizations with their own boards and directors, similar to charters.

The Denver board has also passed several progressive policies, including mandating all-gender restrooms, voting to make the district’s curriculum more inclusive of Black, Latino, and Indigenous history, and removing police officers from schools

The past two years have also seen turmoil and division. Most recently, the board ordered an investigation of sexual assault claims against member Tay Anderson, which were not substantiated. The board voted to censure him for other conduct uncovered by the investigation.

Last year, city leaders blamed a “dysfunctional” school board for pushing out former Superintendent Susana Cordova, who left in late 2020. The board had to hire a new superintendent, Alex Marrero, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Denver Classroom Teachers Association President Rob Gould applauds the union-backed board. Its members have listened to teachers and communities more than past boards, he said.

“We didn’t have that in the 10 years prior,” he said. “That’s what led to the strike: We continuously were talking and saying, ‘This isn’t working, this isn’t working.’ … Moving forward, that’s why we’re excited. And we’re hopeful that Denver will continue to support teachers, teacher voice, and community voice, and really can elect those pro-public education candidates.”

Four seats on the seven-member school board are up for election this year. The union has endorsed current board President Carrie Olson, a former Denver teacher and the only incumbent in the race, as well as Xóchitl “Sochi” Gaytán, a real estate agent and parent; Michelle Quattlebaum, a Denver high school family liaison and parent of three graduates; and Scott Esserman, a parent, former teacher, and district volunteer.

Backlash and big spending

But not everyone is happy with the union-backed board. The chief concern among critics is that the board hasn’t focused enough on academics. Standardized test scores dropped last spring, especially in math, after more than a year of pandemic-interrupted learning. That the trend was seen statewide, and fewer students took the tests than ever before, hasn’t dissuaded several local education advocacy organizations from raising the alarm.

Dan Schaller, president of the Colorado League of Charter Schools, said “a lot of the focus of late has been on adult issues and adult politics, and that has all fundamentally distracted from making sure we are providing high-quality public school options to all kids.”

Alexis Menocal Harrigan, a parent and former district employee, said she’s troubled that the board spends its time dealing with scandals and drama while her son’s teacher had to fundraise to buy an air conditioning unit and air filter for her classroom.

“This board has done some good work,” she said. “I think they could be doing so much more if they didn’t get distracted and sidelined by internal politics and adult politics.”

Menocal Harrigan ran for the school board in 2019 but lost to Anderson. Earlier this week, she registered an independent expenditure committee with the state to “elevate strong leaders running for school board.” Independent expenditure committees can raise and spend unlimited amounts of money in elections but cannot coordinate with the candidates.

Organizations critical of the union-backed board, including the Colorado League of Charter Schools, have contributed heavily to independent expenditure committees. As of Thursday, reform-oriented committees had spent more than $850,000 in support of three candidates: Vernon Jones Jr., Gene Fashaw, and Karolina Villagrana.

Meanwhile, independent expenditure committees funded by teachers unions had spent more than $115,000 in support of the four union-endorsed candidates.

Advocacy group Stand for Children Colorado, whose parent organization contributed $15,000 to a committee supporting Jones, Fashaw, and Villagrana, endorsed those three candidates as well as incumbent Olson. Executive Director Krista Spurgin said the parent committee that made the endorsements liked that the four are educators. While Olson spent her entire career in district-run schools, Jones, Fashaw, and Villagrana have all worked at charter schools. Jones also recently stepped down as executive director of an innovation zone.

Similar to how the group’s endorsements cross traditional battle lines, Spurgin said she hopes the muted rhetoric among this year’s school board candidates is a sign that district politics may be moving away from the polarized place they’ve been.

“This moment ahead of us should be a time for us to figure out how to work together,” Spurgin said. “Our community of reform versus traditional needs to find some middle ground.”

This article was originally posted on What’s at stake in the Denver school board election two years after a historic shift