Rita Jackson had a big new job this year.

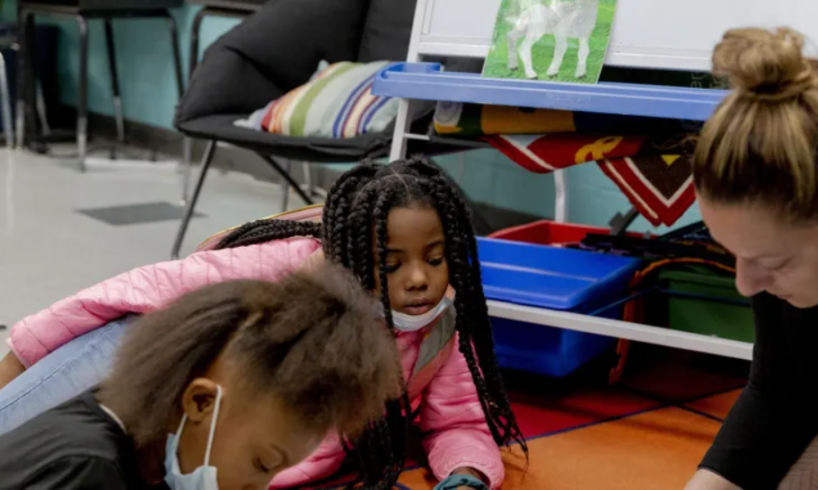

The longtime Baltimore elementary school teacher became a “learning loss interventionist,” working with small groups of struggling students every day. She’s spent the year showing younger students how to put pencil to paper and teaching older students how to craft compelling paragraphs.

With that targeted help, students are “definitely showing growth and gains,” she said. Still, “it was almost like whack-a-mole all year long,” Jackson said.

“COVID numbers are down, but the kids are fighting or they’re not getting along. Then, here go the numbers again, we’re spiking, oh here’s the stress and anxiety. Oh, we have no subs, so no intervention. It’s just constantly something else.”

That will sound familiar to many teachers and students across the U.S. about to wrap up their third pandemic-affected school year. The year marked a return to fully in-person learning for most, but COVID waves, staff shortages, and a sharp rise in student absenteeism meant the school year never quite got back to “normal.” Now, many exhausted teachers and students are counting down the days to summer — while thinking about how the lessons of this year will shape the next one.

“It has taken a toll on everybody to make it this far,” said Alyssa Rodriguez, a school social worker in Chicago. “It’s just going to be a very long finale.”

A rise in teacher absences due to COVID or other illnesses — and a lack of subs to fill in for them — has been a defining feature of this year. Coupled with persistent staffing shortages, the issue has compounded burnout and made it harder for students to catch up, as educators routinely stepped in for missing colleagues while juggling their own classes.

In Hillsborough County, Florida, assistant superintendent Daniela Simic saw how teacher absences weighed on schools. At the start of the school year, Simic said, teachers were asking her team of curriculum specialists lots of questions and using resources they had created to help teachers review skills or knowledge from a prior grade level. But she noticed a drop-off as the school year progressed, especially at schools with more teacher vacancies and absences.

“When you are so exhausted and you are dealing with having to take on three other classes during the day because there’s no substitute teachers available to take the kids, then you kind of revert to what’s easiest,” she said.

Substitute shortages were more common at higher-poverty schools in her district, Simic said, because subs were more likely to choose to work in schools with more affluent students. Those staffing disparities had an effect on student learning.

“That divide continues to grow and grow,” she said.

Student absences also complicated schools’ intervention plans. Many districts have reported a spike in student absences this year, including New York City, Los Angeles, Chicago, Las Vegas, and Memphis.

At Jackson’s school in Baltimore, some students missed school when they got sick or quarantined. In other cases, families kept children home for weeks at a time whenever the city’s positive case rate ticked up.

Jackson understands why the fear has lingered for some families in a majority Black city that’s weathered some 1,800 COVID deaths. Students who are cared for by grandparents are especially worried about getting their family sick. But she also sees the impact. Some of her students have missed 45 to 60 days of school.

“Our kids that aren’t coming to school aren’t getting the intervention and they’re not making growth,” Jackson said. “These are kids that are struggling, and that’s hard.”

In Los Angeles schools, teacher Meghann Seril saw her third graders make strides as they spent more time in the physical classroom.

The gains of one student who struggled to learn math virtually last year have been particularly heartening. Online, the student had a hard time recalling what she’d learned the week before, and she froze up when it came time to start a math problem. Now, Seril sees that student putting objects on her desk to help her count and using the listening strategies they worked on as a class.

But Seril is already eyeing ways to change up her instruction this fall. Third grade teachers at her school decided to put away the devices this year to give their students a break from technology. But sometimes that meant students did less independent learning.

For example, during a recent unit about how Los Angeles has changed over time and how people interact with the natural environment, students wanted to know: “Who takes care of the Los Angeles River?” Seril wished she’d planned for students to get into groups to find the answers to their questions online.

“I definitely want to build in time next year for students to do some of their own research, and to feel a little more empowered,” she said. “I want to swing back a little bit and see how we can get a better balance.”

Seril is also planning to spend some extra time getting to know the second graders who will be in her class next year, so she can tweak some of her lessons over the summer to reflect their interests — whether that be rocks or mythology.

“At the end of last year, I was so exhausted that I did not have the capacity to do this,” she said. “But I have been so re-energized by my experience with my students this year that I feel like I have that little extra that I can give.”

In Chicago, Rodriguez has seen her school nail down exactly when a mental health need is serious enough to require outside help, and how the behavioral health team can best work together to keep a close watch on students in need.

But there are some challenges that have lingered all year. Students are still fighting more than usual, and conflicts escalate quickly if an adult isn’t there to step in.

Come fall, her school is planning a big push to help students work on building friendships, resolving conflicts, and identifying adults they can turn to for help. Her school will be “coming in with very high and strict, concrete expectations,” she said, after a year in which students had a lot of “wiggle room.”

“We really didn’t know what to expect,” Rodriguez said. “We didn’t have as many guardrails as we normally would have had.”

Educators plan to hang reminders throughout the building so students have a clear picture of what happens if they skip their homework or act out in class.

The goal: “Just trying to figure out how we come in strong in the beginning so we’re not necessarily having to have so much discussion on the back end.”

This article was originally posted on This school year never got back to ‘normal.’ These are the lessons educators will carry with them.